This morning I read from the the book of John the story of Christ healing a man who was born blind. The man’s conversation with the Pharisees about his anonymous healer is enlightening. If you are not familiar with the story, the man who had been born blind was healed by the Savior on the

Sabbath. This was an act that was considered by the ruling class of the Jews as not only unlawful, but for which they had already had a confrontation with Jesus earlier (John 5) and were seeking to kill him for it. This healing on the Sabbath only added fuel to the fire. The problem was that the healed man could not identify his benefactor. After questioning the man and even the man’s parents, and after asking him again how his eyes had been opened, the man must have been exasperated, for he retorted that he had already answered them, then asked:

“’Why do you want to hear it again? Do you want to become his disciples, too?’

(John 9:27-30)

Then they hurled insults at him and said, ‘You are this fellow’s disciple! We are disciples of Moses! We know that God spoke to Moses, but as for this fellow, we don’t even know where he comes from.’

The man answered, ‘Now that is remarkable! You don’t know where he comes from, yet he opened my eyes…”

I paused at the reaction of the Pharisees. It made me wonder at how we often cling to our own traditional views and how unwilling we are to consider things outside our own boxes.

How does the example of the Pharisees’ response compare with words of God found in places that we may not recognize as scripture simply because we do not know the author? Can God’s word be found in books we classify as “pseudepigraphal” and reject because we do not know where it comes from?

Pseudepigrapha are falsely-attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. Many works classified as pseudipigraphal were considered by some early Christians as scripture, but were eventually rejected from the canon during christological debates in the early church. I have often wondered about what gems of enlightened wisdom are to be found in some of these writings. For example, words of past prophetic writing is rejected in pseudipigraphal works because the real author attributes the words to some important figure in the past. Yet we don’t see Moses criticized for authoring words of Jacob’s blessing to his sons in Genesis chapter 49.

Must I limit my study only to what is considered canonical to find God in it? Can my eyes be opened from sources where the mortal author is unknown? If I adopt an attitude of accepting truth from wherever it may be found, why limit myself to only one canon of scripture?

“[O]ne should accept the truth from whatever source it proceeds.”

Moses Maimonides, Jewish rabbi, physician, and philosopher, The Eight Chapters Of Maimonides On Ethics, translated by Joseph I. Gorfinkle, pg 35-36

“… Mormonism is truth, in other words the doctrine of the Latter-day Saints, is truth. … The first and fundamental principle of our holy religion is, that we believe that we have a right to embrace all, and every item of truth, without limitation or without being circumscribed or prohibited by the creeds or superstitious notions of men, or by the dominations of one another, when that truth is clearly demonstrated to our minds, and we have the highest degree of evidence of the same.”

Letter from Joseph Smith to Isaac Galland, Mar. 22, 1839, Liberty Jail, Liberty, Missouri, published in Times and Seasons, Feb. 1840, pp. 53–54; spelling and grammar modernized.

“If you shut your door to all errors truth will be shut out.”

Rabindranath Tagore, Stray Birds (1916), pg 130

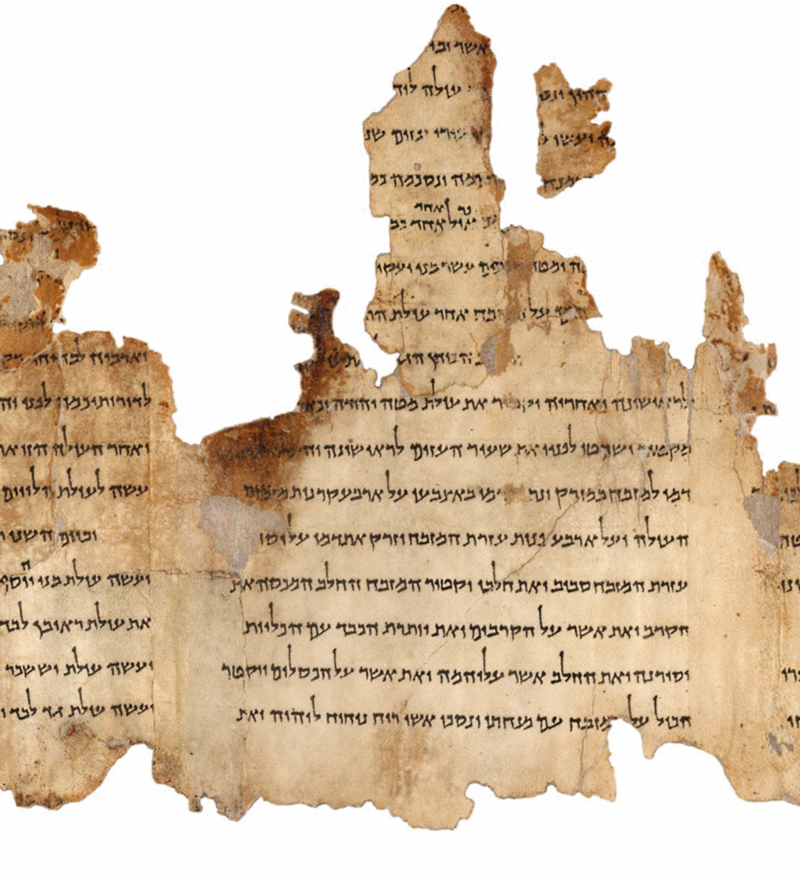

In November of last year, a question arose as I was reading through the Dead Sea Scrolls. The unknown author(s) of many of these ancient documents from Qumran seems to take some amazing liberties with regard to authoritatively giving his own interpretation (often titled “pesher”) or spin on the scripture of his day. In other places the author simply declares the word of the Lord. Take this remarkable passage from cave 4, translated from fragment 4Q371-3:

“I shall praise the Lo[rd that] my meditation [might] be pleasing to Him […] [and] heart, to teach understanding […] judgment, for my word is [swee]ter than honey, [my] ton[gue] more pleasing than wine. [Every word that I speak] is truth, every utterance of my mouth, righ[teousness]. None of these testimonies shall fail, none of these fine promises perish, for all of them […] The Lord has opened my mouth, the words that I speak come from Him. His word is in me, so as to declare [… To us belong] His mercies; He shall not grant His laws to another nation; neither shall He adorn any stranger with them. Surely […] [A]braham, for He made a covenant with Jacob to be with him for all etern[ity…”

Portion 4, lines 4-9, as quoted from Dead Sea Scrolls, A New Translation, by Michael Wise, Martin Abegg Jr., & Edward Cook p. 334

Compare the audacious words of this author with this passage we read from Isaiah in the Bible:

I clothe the heavens with darkness

and make sackcloth its covering.

The Sovereign Lord has given me a well-instructed tongue,

to know the word that sustains the weary.

He wakens me morning by morning,

wakens my ear to listen like one being instructed.

The Sovereign Lord has opened my ears;

I have not been rebellious,

I have not turned away.

…

Because the Sovereign Lord helps me,

I will not be disgraced.

Therefore have I set my face like flint,

and I know I will not be put to shame.

He who vindicates me is near.

Who then will bring charges against me?

Let us face each other!

Who is my accuser?

Let him confront me!

It is the Sovereign Lord who helps me.

Who will condemn me?

They will all wear out like a garment;

the moths will eat them up.

Isa 50:3-9, NIV

Here Isaiah begins with words that are a direct quote from God. If you were completely unfamiliar with Isaiah and were reading this for the first time, these statement could seem quite bold (or course, it is bold even when you are familiar with Isaiah). These words not only apply to Isaiah himself, but are prophetic words that apply to Christ.

How are the words from the unknown author in the Dead Sea Scrolls different from the bold testimony we see written by Isaiah? Was this person from Qumran inspired like Isaiah (or Jeremiah, or David, or Paul)? Why couldn’t I accept these words as scripture? For me, I am inspired by these words. I feel like exclaiming, “Now that is remarkable! We don’t know where he comes from, yet he opens my eyes.”