Book review by Jay Ball

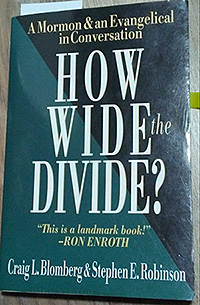

I just finished reading “How Wide the Divide, A Mormon & an Evangelical in Conversation” by Steven Robinson from BYU and co-authored with a member of the Evangelical-based Denver Theological Seminary faculty, Craig Blomberg. (In the following article, page references without any other citation are to this book.)

As an LDS reader, my first reaction to the book is to applaud that this conversation takes place between anyone of differing denominations.

As an LDS reader, my first reaction to the book is to applaud that this conversation takes place between anyone of differing denominations.

Like Paul in Philippians 4:2 pleading with Euodia and Syntyche to “agree with each other in the Lord” (NIV), or “be of the same mind” (KJV), I think there is value in finding common ground wherever two or more can gather in His name (see Matt 18:20).

I thought these remarks in the concluding chapter made a good summation of the book:

“As we have made clear throughout this book, we do not claim to have settled all of our differences. Neither do we believe that Mormons and Evangelicals would, or even ought to, accept one another’s baptisms. We harbor no delusions that this modest dialog will in any way diminish the extent to which LDS missionaries bear testimony to Evangelicals or to which Evangelicals witness to Mormons, nor do our respective beliefs convince us that such activity should diminish. But we can hope and pray that as sincere, spiritual men and women (who all claim the name of Christ) talk about their beliefs and life pilgrimages with each other, they might do so with considerably more accurate information about each other and in a noticeably more charitable spirit than has often been the case, after the pattern set by common intent of both ‘sides’ to confess, to worship, and to serve that Jesus Christ who is described in the New Testament as our Lord…

Might we look forward to the day when youth groups or adult Sunday-school classes from Mormon and Evangelical churches in the same neighborhoods would gather periodically to share their beliefs with each other in love and for the sake of understanding, not proselytizing?” (How Wide the Divide, p. 190-191)

As with any good discussion, there is value in what we can learn from each other in the process, particularly as it may enlighten our understanding about things that matter most. I admire how the two authors often disagreed with each other in a way that was not harsh or contentious. This I feel is a sign of a good and healthy discussion. It is with such a spirit I add my own commentary to this discussion.

As I often do, I made observations in the margins as I read. One thing I think that surprised me most is Robinson’s focus and desire that Mormons be accepted as Christian. Part of me agrees with his argument:

“If Armenian and Calvinist Evangelicals can disagree over free will, election, irresistible grace, eternal security and so on, and yet both be deemed Christians, I don’t think merely believing in a subdivided heaven or believing that Jesus can save even the dead should get the LDS thrown out of Christendom.” (Robinson, p. 154)

On the other hand, I see value in LDS just conceding the point and proudly acknowledge we are NOT part of Historic Christianity. We disagree with Historic Christianity, and at a fundamental level we denounce it as false. We claim to be a restoration of Primitive Christianity. We do not share in accepting the creeds which Christ to Joseph Smith denounced as “an abomination in His sight.” (Joseph Smith History 1:19.)

Oddly, from the LDS end, we try and avoid the argument, fit in, claim we are “good Christians too,” and part of the larger community of churches. We try to make ourselves seem more like Historic Christianity, and avoid or discard what once set us apart.

On LDS Orthodoxy

In his effort for Mormons to be accepted as Christian, Robinson makes a point to establish certain things as agreeing with (or not) to a standard Mormon orthodoxy, as if there was such a thing.

“By and large the LDS do not worry as much about orthodoxy within their own community as do Evangelicals, though there is such a thing as LDS orthodoxy. In short run, LDS orthodoxy is defined by the Standard Works of the Church (Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price) as interpreted by the General Authorities of the Church – the current apostles and prophets.” (p. 15)

The phrase “LDS orthodoxy” seems like a bit of an oxymoron to me. We have no ‘orthodox’ creed in Mormonism. We welcome all truth, from whatever source. We have the following statements in our scriptures:

“We claim the privilege of worshiping Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience, and allow all men the same privilege, let them worship how, where, or what they may.” (11th Article of Faith)

Despite this, Robinson continues to assert “official LDS teaching” in his discussion on various topics.

“The official doctrine of the Church on deification does not extend in essentials beyond what is said in the Bible, with its Doctrines and Covenants parallels.” (Robinson, p. 85)

One important LDS cannon of “official doctrine” that Robinson has missed giving any reference to is Lectures on Faith which was never “officially” removed from the cannon (i.e. it was removed from the cannon without a vote). See BYU publication by Larry E. Dahl, Authorship and History of the Lectures on Faith. Speaking about the Lectures on Faith Bruce R. McConkie said “It was written by the power of the Holy Ghost, by the Spirit of Inspiration. It is in effect, eternal scripture. It is true.” (The Lord God of Joseph Smith, discourse delivered January 4, 1972)

Robinson states that “it is the official teaching of the LDS Church that God the Father has a physical body (Doctrine and Covenants 130:22).” (p. 87) Though I don’t disagree with this as coming from an “official” LDS source, in fairness we must also recognize that “The Father is a personage of spirit, glory, and power” as taught in Lectures on Faith 6, paragraph 2.

Speaking for Latter-day Saints, Robinson says that “it irritates the LDS that some Evangelicals keep trying to add the Journal of Discourses or other examples of LDS homiletics to the canon of LDS Scripture.” (p. 73)

I have wondered if it shouldn’t be equally irritating that what is currently taught over the pulpit in General Conference is considered LDS Scripture.

Blomberg later was quick to observe:

“Robinson insists that the Adam-God theory, as proposed by the various interpreters of Brigham Young, makes no sense and was never officially endorsed. These clarifications would seem to hold the door open for significant rapprochement between Evangelicals and Mormons on these doctrine, especially if the LDS can continue to avoid using unofficial statements from their past to define present official LDS doctrine.” (P. 109, emphasis mine.)

Adam-God theory was endorsed over the pulpit by Brigham Young in general conference of the Church. Would that not make it both “official” and “endorsed”?

Brigham Young taught over the pulpit and in conference talks, Adam-God theory, polygamy as essential to salvation, and, the day we accept blacks into priesthood will be the day the Church is in apostasy. Yet today the Church denies these are doctrines.

“[W]e can’t logically assert that pronouncements made by prophets today are to be automatically accepted, without question and testing by the Spirit and other standards as the “mind and will of the Lord,” yet discount the unacceptable teachings of former prophets in this dispensation as being only personal views. The same standard must apply – how we regard the statements of prophets on doctrinal matters today is how we must regard the doctrinal statements of prophets who lived a century ago, and vice versa.” (Duane S. Crowther, Thus Saith the Lord, 1980, p 236)

I don’t point this out to be contrary or argumentative. I only want to make the point that we should not be too quick to declare what is “official LDS teaching”. As Robinson rightly observes:

“Pure LDS orthodoxy can be a moving target, depending on which Mormon one talks to.” (p. 14)

On LDS Scripture

Robinson later states:

“For Latter-day Saints, the Church’s guarantee of doctrinal correctness lies primarily in the living prophet, and only secondarily in the preservation of the written text.” (p. 57)

Personally I know of no “guarantee of doctrinal correctness” in the Church.

Church President Joseph Fielding Smith wrote:

“It makes no difference what is written or what anyone has said, if what has been said is in conflict with what the Lord has revealed, we can set it aside. My words, and the teachings of any other member of the Church, high or low, if they do not square with the revelations, we need not accept them. Let us have this matter clear. We have accepted the four standard works as the measuring yardsticks, or balances, by which we measure every man’s doctrine… If Joseph Fielding Smith writes something which is out of harmony with the revelations, then every member of the Church is duty bound to reject it.” (Doctrines of Salvation, 3 vols., edited by Bruce R. McConkie [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954-1956], 3: 203.)

On page 58, Robinson comments that one role of an apostle is: “he is necessary to authoritatively interpret [the written word of God]”. I believe an apostle/prophet’s role has more to do with crying repentance* and leading men to make their own connection with heaven than “authoritatively interpreting” scripture. The expectation that we must rely on some man with authority to interpret scripture for us misses the point of the purpose of scripture. I previously wrote about this:

“The purpose of scripture is to lead us to Christ, to have His [law] written in our hearts (Heb 10:16), and make Him alive in us (Eph 2:5). Despite the claim that the scriptures alone save, we can’t ignore the promise of scripture that God will continue to speak to man. (James 1:5-6; Joel 2:28-32) If the Bible does not ultimately lead us to Christ, what purpose does it serve? The objective is to come to Him, not the Bible (or a prophet). Scripture is a means, not an end. What difference is there between a Mormon who blindly follows a prophet that he assumes cannot lead him astray, and a Christian who blindly assumes that scripture alone can save by trusting in the word alone, without getting a witness from God Himself? The missing element in both is the personal connection with Christ. Do I turn to Him? Do I know His voice? (John 10:27)”

In Robinson’s eagerness for Mormons to be accepted as Christian among the Evangelical community, he inadvertently reveals something about the “vanity and unbelief” of the LDS Church, for which the Lord in September of 1832 declares “the whole church under condemnation.” (See D&C 84:54-57.)

“[T]he King James Bible is the LDS Bible. No other version, not even the JST [Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible], supplants the KJV.” (Robinson, p. 59)

I agree with Robinson’s assessment but I would ask why this is so? As recent as 1993 Elder Oaks has reaffirmed that it is because of neglect and treating lightly the things given through Joseph Smith that “has continued the condemnation in our own day.” (Another Testament of Jesus Christ, Dallin H. Oaks BYU Fireside June 1993.) If the Church is under condemnation for treating lightly what was given through Joseph, why do we continue to hold the KJV in higher esteem than the JST?

“Leaders of the LDS Church from Joseph Smith to the present have tended to use the Bible even more than the Book of Mormon in their teaching and preaching.” (Robinson, p. 59)

The historical LDS neglect for the Book of Mormon is not realized by most Latter-day Saints today. For example, from the founding of Brigham Young University in 1875 until 1937, there was not a single course offered on the Book of Mormon at BYU. It was not until 1961 the Book of Mormon became a required course for all BYU freshmen.

“The first fully developed Book of Mormon class was offered in 1937 by Amos Merrill. Introduction of this course faced considerable resistance from some department administrators, remembers Hugh Nibley, and key faculty members wondered how the Book of Mormon could be taught for a whole semester.” (Reynolds, Noel B. The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon in the Twentieth Century, BYU Studies, 1999)

Working in a climate of intellectual hostility, Hugh Nibley is given credit for being responsible for much of the change in focus to taking the Book of Mormon seriously in the Church and is highly commended by Neal A. Maxwell. You can read Noel B. Reynolds complete publication here.

In their joint conclusion of Chapter 1, Blomberg and Robinson assert, “We further agree that JST variants do not necessarily imply that the KJV text is corrupt.” (p. 75) If the JST “variants” don’t imply this, the Book of Mormon certainly does. The Book of Mormon says of the Bible that many covenants have been taken away from it (1 Nephi 13:26), and that the right ways of the Lord might be perverted to blind the eyes and harden the hearts of the children of men (v 27). Plain and precious things have been taken from it (v 28) and because of this many do stumble and Satan has great power over them (v 29).

All this aside, the Bible is still acknowledged as important scripture to Latter-day Saints.

“It is [the orthodox churches] post biblical creeds that are identified in Joseph Smith’s first vision as an ‘abomination,’ but certainly not their individual members or their members’ biblical beliefs.” (Robinson, p. 61)

That Joseph Smith didn’t have anything but the Bible to go by when he went to the woods to pray, gives evidence that (even if you are a believing Mormon) one can find God by trusting in the word of the Bible alone.

“In the Washington lecture, Joseph underscored beliefs held in common with other Christians. ‘We teach nothing but what the Bible teaches. We believe nothing, but what is to be found in this Book.’ … Joseph insisted more than once that ‘all who would follow the precepts of the Bible, whether Mormon or not, would assuredly be saved.’” (Richard Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, p. 195)

On Salvation

In Chapter 1 on Scripture Robinson states,

“In the LDS view the fullness of the gospel is ultimately necessary to salvation, but not necessarily in this life.” (Robinson, p. 73, emphasis mine.)

I agree with Robinson that one way the term “fullness of the gospel” is used in scripture is as a way to identify Christ revealing Himself to mankind, thereby redeeming mortals from the fall, as we read in D&C 76:14. Later in this section we read how this is something intended for us to experience “in the flesh” (v 118), or in other words in this life (see Alma 34:32).

Later Robinson continues to justify the idea that we can procrastinate the day of our repentance** and still come out OK in the end:

“[W]e believe the gospel is preached to the ignorant and rebellious spirits (pneumata) in prison, that they may repent and accept Christ and live (Jn 5:25-29; 1 Pet 3:18-20; 4:6). Like the prodigal son of the parable, they may yet reconsider, repent and be joyfully received among the mansions of the Father although perhaps not to receive all that will be inherited by the more faithful.” (p. 150)

Robinson is touching upon a topic about which Nephi could well be warning us as Latter-day Saints in 2 Nephi 28:8:

“And there shall also be many which shall say: Eat, drink, and be merry; nevertheless, fear God—he will justify in committing a little sin; yea, lie a little, take the advantage of one because of his words, dig a pit for thy neighbor; there is no harm in this; and do all these things, for tomorrow we die; and if it so be that we are guilty, God will beat us with a few stripes, and at last we shall be saved in the kingdom of God.” (As an aside, reference to “Zion” in verses 21 and 24 is another indication this warning can apply to Latter-day Saints.)

“Mormons believe the saved will be divided into three broad divisions called kingdoms or glories. The lowest of these is the telestial glory.” (Robinson, p. 152)

In this view, all but those who become “sons of perdition” are “saved”. Viewed another way, however, “damnation” is to cease progressing or to regress. Anything less than the Celestial Kingdom has an end, beyond which we cannot have an increase (see D&C 131:4).

“The LDS believe there will be millions, even billions, of good souls who will come from the east and the west to sit down with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in the celestial kingdom.” (Robinson, p. 153)

I frankly don’t know where Robinson gets this idea or how to reconcile it with Matt 7:14, “Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.”

At its core, the definition of salvation is getting to know the Lord. (John 17: 3). Yet Blomberg argues:

“[S]hould we not expect an omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent God not to be fully comprehensible by mere mortals?” (Blomberg, p. 121, along with its footnote 31 on p. 217, which says: “Augustine once wrote, ‘If you can understand it, it’s not God'”.)

Although written by one who is now excommunicated from the LDS Church, I still like how this author poses it:

“The doctrine of the Trinity which was settled, if not created, in the Council of Nicea is an impediment, and not an advantage, to knowing God. If ‘life eternal’ is to ‘know God’ (as John declared–see John 17:3) then of what value is a doctrine that makes God ‘incomprehensible?'” (Denver Snuffer, Trinitarian Impediment)

Joseph Smith elaborates on what salvation means in Lectures on Faith. (See Lecture 7.)

“And for any portion of the human family to be assimilated into their [God the Father and the Son’s] likeness is to be saved; and to be unlike them is to be destroyed: and on this hinge turns the door of salvation.” (para 16)

Nephi adds, “He that endureth to the end, the same shall be saved. And now, my beloved brethren, I know by this that unless a man shall endure to the end, in following the example of the Son of the living God, he cannot be saved.” (2 Nephi 31:15-16)

Robinson claims that Mormons believe, like the Evangelical, that Christ first saves us, and then transforms us to be like Him:

“Latter-day Saints believe that God intends through the gospel of Jesus Christ to transform those who are saved by Christ to be like Christ.” (Robinson, p. 80)

Later Robinson acknowledges the role grace plays in our path to salvation:

“To Latter-day Saints the glorified and resurrected Christ illustrates in his person what the saved can become through his grace.” (Robinson, p. 81)

For me, the subject of how grace relates to salvation is easier to grasp when I understand that Mormons and Evangelicals define grace differently. When I view grace as not only “unmerited favor”, but also includes the gift or power to become more like Christ (Strong’s Concordance 5485: grace as a gift or blessing, favor, kindness), then it’s easier to appreciate how the two groups treat this word differently.

Seeing grace as “an enabling power to move closer to God”, or as “an increase of light” helps explain:

“It is by grace we do the required works to be saved. As explained in Philip. 2:13: “For it is God which worketh in you both to will and to do his good pleasure.” As Paul explained in Romans 6:1-2 concerning those who are born again through Christ: “What shall we say then? Shall we continue in sin, that grace may abound? God forbid.” We must escape sin by the grace of God and then do the works that testify we are in possession of God’s grace. As James explained in James 2:17-20: “Even so faith, if it hath not works, is dead, being alone. Yea, a man may say, Thou hast faith, and I have works: shew me thy faith without thy works, and I will shew thee my faith by my works. Thou believest that there is one God; thou doest well: the devils also believe, and tremble. But will thou know, O vain man, that faith without works is dead?” If we are saved by the grace of God our works will testify of that grace within us. Without the works of righteousness, put within us by being born again, a new creation of Christ’s, we may claim to have been saved by grace, but it is without proof.” (Denver Snuffer, Are We Saved by Grace or Works?)

As Robinson and Blomberg jointly concluded in Chapter 4:

“If we do not demonstrate good works, some sign over time, of a changed life, our professions of faith are ultimately futile.” (p. 187)

Moving On…

I try to resist contentious debate, so there is a certain level of inner conflict I grapple with as I try to avoid being too critical. But it was difficult to resist the temptation to engage the challenge Blomberg invited with the use of phrases like “there is not a shred of historical evidence…”, “No early Christian theologian ever…”, or “all agree…”. My purpose has been to call out what I see as I read the book, so although I do not include all my observations, I’ve chosen to point out the few that stood out most.

“[A]ll these Christian concepts included in the pre-Christian stories of the Book of Mormon were supposedly known in earlier times. The trouble is that there is not a shred of historical evidence from the ancient world that the suppression of such literature ever took place. It defies imagination how every hint of the vast panorama of New Testament texts and concepts could have disappeared from both the Old Testament and other pre-Christian Jewish documents, even had a censor deliberately tried to destroy it all.” (Blomberg, p. 49)

Margaret Barker, bible scholar, author of 17 books, and Methodist preacher, provides a good amount of scholarly historical evidence of precisely the very thing that “defies [Blomberg’s] imagination”. She has written much on how “King Josiah changed the religion of Israel in 623 BC… King Josiah’s purge is usually known as the Deuteronomic reform of the temple.” (See What Did King Josiah Reform? Presented 6 May 2003 at Brigham Young University).

The topic can be debated, but to suggest there “is not a shred of historical evidence” that suppression of ancient scripture took place is simply incorrect.

On Polytheiphobia

Blomberg’s position on polytheism is understandable. This is a fundamental belief of most modern Christian religions.

“At this point we find ourselves face to face with polytheism, which the Bible defines as idolatry.” (Blomberg, p. 105)

“[T]he most crucial observation about God to be gleaned from the Old Testament is its unrelenting monotheism.” (Blomberg, p. 113)

I’m surprised, however, at Robinson’s attempts to distance himself from the negative connotation of the term polytheism:

“Thus there are three divine persons, but only one Godhead. Clearly Prof. Blomsberg feels that such a Godhead is unlikely and that defining the Godhead so runs a risk of polytheism – but that is not the LDS belief. It would horrify the Saints to hear talk of ‘polytheism.’” (Robinson, p. 132)

Many LSD scholars argue that the earliest form of Judaism was not monotheistic. The “Elohim” of the Old Testament was plural. Hence the English translation of “God” (in Hebrew “Elohim” a plural noun) saying “Let us make man in our image.” To be true to the text it was necessary to employ a plural pronoun. Therefore, right at the beginning of the scriptural text God is plural.

“Whom do we believe? Do we work with the picture of a pagan religion which the Deuteronomists reformed and brought back to pristine purity, or do we work with a picture of an ancient religion virtually stamped out by the Deuteronomists, who put in its place their own version of what Israel should believe? This question is not just academic, a fine point to be debated about the religions of the ancient Near East. Our whole view of the evolution of monotheism in Israel depends on the answer to this question, for the Deuteronomists are recognized as the source of the ‘monotheistic’ texts in the Old Testament and as the first to suppress anthropomorphism. If the Deuteronomists do not represent the mainstream of Israel’s religion (and increasingly they are being recognized as a vocal minority), was the mainstream of that religion not monotheistic and did it have anthropomorphic theophanies at its centre?” (Margaret Barker, The Great Angel, 1992, p. 14)

On Jesus as Son of God the Father

In Chapter 2 footnote 28, Blomberg writes:

“In some of the literature I read, Jesus’ references to himself as ‘Son of Man’ were used as further support for the physicality of God the Father. But this was an established Hebrew idiom, used to mean ‘human’ (see throughout the book of Ezekiel), including a quasi-messianic title for a very exalted human (in Dan 7:13-14). While a massive debate among Bible scholars of all traditions rages as to which of these backgrounds is more important for Jesus’ use of the term, all agree that it predicates nothing about the God who is Jesus’ Father.” (p. 213)

I would say not “all agree”. Quoting Margaret Barker again:

“Matthew records Jesus’s own version of the judgement theme in Matt. 25.31-46. The language is very revealing, as are the presuppositions that scholars bring to it. The Son of Man comes with his angels and takes his place on the throne as judge. He is the King acting for another whom he names as his Father (Matt. 25.34). There is no need to suggest that the ancient role of Yahweh the King has been altered and given to the Son of Man, thus causing complications and making it necessary for Matthew to alter the story so as to make a place for ‘the Father’:

‘In verse 34 [of Matt 25] the Son of Man is referred to as ‘the king’. This may be a trace of an earlier state of the parable, in which the reference was to God himself. If so, the address to those on the right hand as ‘blessed of my Father’ must be regarded as a Matthaean adjustment.’ (B. Lindars, Jesus Son of Man, London 1983, p. 126)

None of this is necessary if we recognize that Yahweh was the Son of Elyon, the Man. The Son of Man as vicegerent is exactly like the role of Philo’s Logos and this is corroborated in Mark 2.10 and parallels where the Son of Man has authority to forgive sins on earth and in John 5.27 where the Father has given authority to the Son of Man to act as judge. Mark hints at this identification of Yahweh and the Son of Man in Mark 2.28; the Son of Man is Lord even of the Sabbath.” (The Great Angel, 1992, p. 226)

In Chapter 3 on Christ and The Trinity, Blomberg challenges that:

“No early Christian theologian ever identified Jesus as a completely separate God from Yahweh, Lord of Israel. ‘Son of God’ in it’s Jewish context was a messianic title (see Ps 2; 89; 2 Sam 7:14) and was never taken to suggest that Jesus was the literal, biological offspring of his heavenly Father.” (p. 116)

I don’t know about early Christian theologians, but:

“Several writers of the first three Christian centuries show by their descriptions of the First and Second persons of the Trinity whence they derived these beliefs. El Elyon had become for them God the Father and Yahweh, the Holy One of Israel, the Son, had been identified with Jesus.” (Margaret Barker, First sentence of Chapter 10 titled “The Evidence of the First Christians” from The Great Angel, p. 190. The entire chapter is about this subject. I would commend it to anyone who has a desire to pursue the topic further.)

To Conclude

Finally, there were several places that I underlined without commentary because I simply agreed with the text.

I thought this was a fair observation by Robinson:

“[B]ut [Joseph Smith] cannot be accused of contradicting the Bible where the Bible is silent. There are gaps. I would be quite happy to have Evangelicals say to me, ‘You Latter-day Saints have beliefs and doctrines on subjects about which the Bible is silent or ambiguous.’ That is a fair statement. However, I believe it is unfair to say, ‘Since you hold opinions where the Bible is silent, you contradict the Bible,’ or, ‘Because you contradict Nicaea and Chalcedon, you contradict the Bible.’” (p. 86)

Amen to this insightful comment by Blomberg:

“[W]e cannot claim to have really surrendered control of our lives to Jesus if we consciously refuse to obey him in certain areas of our lives. We have to be willing, at least in principle, to turn over everything to him. The paradoxical conclusion that perhaps captures the correct balance here is that ‘salvation is absolutely free, but it will cost us our very lives.’ Our old natures must be crucified with Christ regularly.” (p. 169)

One last word

This statement by Robinson & Blomberg in the Joint Conclusion of book caught my attention:

“Many of these characteristics [of what defines a ‘cult’] no longer apply to Mormonism” (p. 193)

“No longer apply”, suggesting that they once did? What characteristics did at one time apply in the past that “no longer apply” now?

I have addressed this topic in an article of its own – Do I Belong to a Cult?

* “As I have sought direction from the Lord, I have had reaffirmed in my mind and heart the declaration of the Lord to ‘say nothing but repentance unto this generation.’ (D&C 6:9; D&C 11:9.)” (President Ezra Taft Benson, Cleansing the Inner Vessel, April General Conference, 1986)

** “And now, as I said unto you before, as ye have had so many witnesses, therefore, I beseech of you that ye do not procrastinate the day of your repentance until the end; for after this day of life, which is given us to prepare for eternity, behold, if we do not improve our time while in this life, then cometh the night of darkness wherein there can be no labor performed.” (Alma 34:33)