[Note: I created an updated version of this model on 19 June 2024 titled Jay’s Learning Model Revisited.]

“A position that begins with an inflexible conclusion and seeks ‘evidence’ to support it is impervious to reason”

This is a quote that I have adapted from something written by Steve Cuno over five years ago. He has since removed the statement from his site, but not before it left it’s impact on my mind. I added the word “inflexible” to the statement so that it more correctly reflects truth.

This quote was the impetus for the creation of the following model. I’ve developed this tool to help explain how I prefer to confront new information that I am faced with.

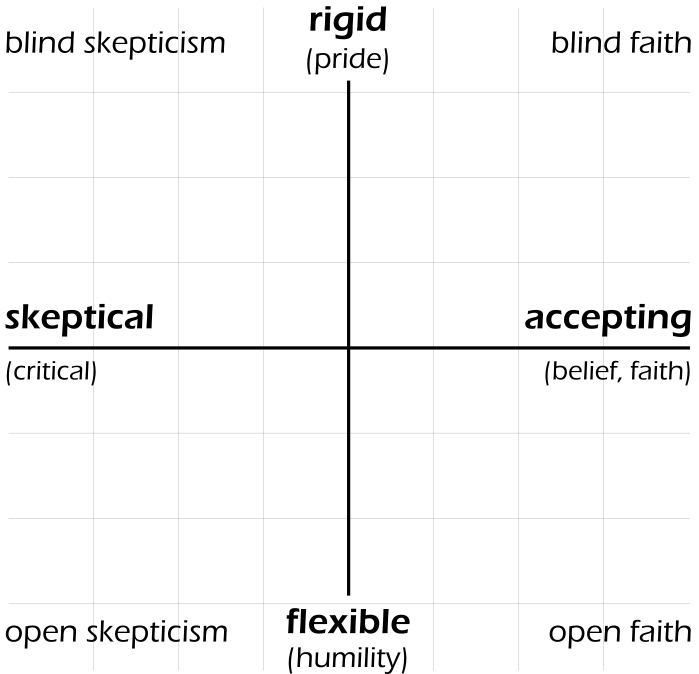

At the top I have labeled “rigid”, and the bottom I have identified with “flexible”. A person can find themselves leaning toward one extreme or the other on any given subject. Dividing this line in the middle, on a horizontal axis, to the far left I have given the label “skeptical”, and to the far right, “accepting”. When presented with new information one can approach any given topic with a perspective ranging from being skeptical about it to being more inclined toward believing and accepting it. It is valuable to consider where you fall in this spectrum when confronted with new information.

The top of the model can be epitomized with this quote from Mark Twain:

“Loyalty to petrified opinion never broke a chain or freed a human soul.”

Or this one:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you in trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The top left quadrant I have identified as “blind skepticism” while the top right is labeled “blind faith”. Either way, it should be evident that neither method is considered a good approach to learning. A sincere student of truth should seek to orient him or herself toward the flexible end of the model. The bottom left quadrant I have designated “open skepticism” while the bottom right is “open faith”.

In LDS scripture we read:

And as all have not faith, seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; yea, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom; seek learning, even by study and also by faith. (D&C 88:118)

What this tells us is that the preferred method of learning is by faith. But “as all have not faith”, then seek diligently to learn from best books etc., while still striving to employ faith in the process. In other words, learning from a skeptical frame of mind is still a useful model, as long as you can remain flexible and allow your thinking to be influenced by truth. Be willing to let go of what is false. Always approach learning with the intent to move toward the bottom right of the quadrant in the above model.

Another example of this idea is given by Alma in the Book of Mormon. What Alma is asking us to do (in Alma 32) is something different than how we are taught in school. Alma was saying, “Hey, why don’t you just experiment with this thing, and plant it as if you believed it. Plant it as if you had faith in it. So forget about the pros and cons, accept the Book of Mormon at face value, and let the Book of Mormon define itself; let the Book of Mormon be the source from which you evaluate whether or not it enlightens you, whether or not it appeals to your heart, to your soul, and to your mind.” Or, if you are not Mormon, use the Bible, or whatever other Holy Book that you trust as foundational to your faith.

For the non-Mormon Christian audience, we see ample evidence from the Bible that support these ideas as well.

For we walk by faith, not by sight. (2 Cor 5:7, see also 1 Thes 2:13)

Apply thine heart unto instruction, and thine ears to the words of knowledge. (Proverbs 23:12)

There are a number of ways that faith can be defined. In the context of this model, I’m defining faith as a principal of action. Faith is the moving cause of all we do. The principal that excites or gives energy to any activity or pursuit, mental or physical, is motivated by what I am referring to here as faith. Would you exert yourself to pursue any activity unless you believed it would return the desired result? As Napolean Hill defined it in his book Think and Grow Rich:

Faith is the ‘external elixir’ that gives life, power, and action, to the impulse of thought.

To this I would add that faith, as a moving cause of action, is not limited to temporal concerns, but applies to spiritual concerns as well.

But without faith it is impossible to please him: for he that cometh to God must believe that he is, and that he is a rewarder of them that diligently seek him. (Heb 11:6)

For these reasons I submit that the preferred method of learning is by faith, but that as long as you can be flexible in your approach, a skeptical frame of mind is still a useful model for discovering truth.

The top of the model could be represented simply with a period. The period closes the sentence. A period makes a statement, dot, the end. No more to be said, no more to learn, no more divine wisdom to be gained.

The bottom of the model, on the other hand, could be represented with a question mark. A question mark opens. It’s only when we ask questions that we get answers.

On the left is a skeptical approach to learning. Many fear (and justifiably so) being taken advantage of. The critical approach is employed to protect against this. The right side of the model represents an accepting or believing approach. This may seem counterintuitive to the skeptic, but it is precisely this approach that is encouraged in many religious texts and spiritual practices.

Read the following statement by Hugh Nibley and consider the top of the model where you see “blind skepticism” and “blind faith”:

If I come down and say, “I just saw a polar bear in Rock Canyon,” what are you supposed to say? “If you say you saw a polar bear in Rock Canyon, Brother Nibley, I believe you.” Well, that’s terrible. I don’t want to hear that. That takes all the wind out of my sails. I want you to go up and see for yourself. Or you might say, “Of course, there’s no polar bear. You didn’t see anything of the sort. No polar bears are found below a certain latitude. Polar bears just aren’t found in these regions, so you didn’t see any polar bear.” Well, I might have; there might have been one that escaped from the zoo. But you don’t know. The thing for you to do is not just take it because I say so, or not to reject it because you are being scientific and you don’t think it can be possible. Find out for yourself.

Hugh Nibley, Teachings of the Book of Mormon, Semester 2, pg 351-352

The bottom quadrants of the model encourage exploration and application. As John Seel writes:

We learn best from experience that captures our imagination and which we subsequently reflect upon analytically: hand, heart, and head.

The New Copernicans, page 23

The left bottom quadrant is where I would place the working principal of knowledge, as oppose to wisdom to the right. By way of illustration, there is value in the knowledge gained by dissecting a frog to learn about its organs, muscles, and bones. But approaching it from the bottom right quadrant, there is much wisdom gained from appreciating the beauty of the living frog – hearing its song, observing how it moves, or trying to capture its color on canvas.