A Comparative Study

Introduction

I’ve always recognized the significance of relationships and interpersonal dynamics. This understanding seems to resonate with the authors of the two books that I am comparing in this post, as they have devoted considerable effort to writing and publishing on this topic:

"When we first published Crucial Conversations in 2002, we made a bold claim. We argued that the root cause of many — if not most — human problems lies in how people behave when we disagree about high-stakes, emotional issues. We suggested that dramatic improvements in organizational performance were possible if people learned the skills routinely practiced by those who have found a way to master these high-stakes, crucial moments." (Grenny, Joseph; Patterson, Kerry; McMillan, Ron; Switzler, Al; Gregory, Emily. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High, Third Edition (Preface, ix). Kindle Edition. References throughout the rest of this paper will be abbreviated to the format, "CC, page no.")

"Personal reality always contains a story, and the story we live, beginning from infancy, is based on language. This became the foundation of Marshall’s approach to conflict resolution, getting people to exchange words in a way that excludes judgments, blame, and violence." (Rosenberg, Marshall B.; Chopra, Deepak. Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life: Life-Changing Tools for Healthy Relationships (Forward, xiii). References throughout the rest of this paper will be abbreviated to the format, "NVC, page no.")

"Believing that it is our nature to enjoy giving and receiving in a compassionate manner, I have been preoccupied most of my life with two questions: What happens to disconnect us from our compassionate nature, leading us to behave violently and exploitatively? And conversely, what allows some people to stay connected to their compassionate nature under even the most trying circumstances?" (Opening paragraph, NVC, 1)

The primary purpose of both books is to highlight the importance of navigating the complexity of our relationships using the only real tools we have to interact: through communication. While in some utopian future state we might evolve to communicate telepathically, for now, we are limited to language. Communication, however, involves more than just words. It’s important to recognize that when discussing communication, we are trying to convey the ideas that motivate and drive our actions.

"Each of us enters conversations with our own thoughts and feelings about the topic at hand. This unique combination makes up our personal pool of meaning. This pool not only informs us, but also propels our every action." (CC, 26)

Why this study?

I have been deeply engaged in studying Marshall Rosenberg’s book, Nonviolent Communication, for over six months. I am impressed with Rosenberg’s work and the insights and understanding it offers on how to address the root of any conflict I encounter. The practical tools provided for interacting in healthy and meaningful ways with others have been delightfully enlightening. In October, I shared my enthusiasm with a friend. He mentioned that it sounded much like a similar book on this subject titled Crucial Conversations. I had heard of this book. It had been recommended to me by several others over the years, but I had not yet managed to fit it into my reading schedule.

Rosenberg’s book has left me with a strong impression that what he provides are key principles, that once understood, I could use to measure the validity and utility of any other work about interpersonal communication. Naturally, I became curious about how the highly endorsed Crucial Conversations compares with Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (hereafter abbreviated “NVC”). I told my friend that Crucial Conversations (hereafter abbreviated “CC”) had been on my reading list, so I committed to read it, compare the two, and share my findings with him. This post is the result of my study.

Get to the root before attempting to strategize solutions.

Most of our communication focuses on identifying what’s wrong, and then attempting to fix it. Rosenberg, however, suggests that it’s not until we are able to identify our feelings and become aware of our true needs, can we begin to offer strategies for resolving differences.

This idea is well put in his chapter on “Conflict Resolution and Mediation”:

"In my experience, connecting people at this level isn’t psychotherapy; it’s actually the core of mediation because when you make the connection, the problem solves itself most of the time. Instead of a third head asking, 'What can we agree to here?,' if we had a clear statement of each person’s needs — what those parties need right now from each other — we will then discover what can be done to get everybody’s needs met. These become the strategies the parties agree to implement after the mediation session concludes and the parties leave the room. When you make the connection, the problem usually solves itself." (NVC, 163-164)

Rosenberg’s NVC Process

The principle sounds simple enough, but a lot of practice is needed. We need to train ourselves how not to think judgmentally, or in other words, violently. Rosenberg’s NVC process involves focusing on four key areas:

"To arrive at a mutual desire to give from the heart, we focus the light of consciousness on four areas — referred to as the four components of the NVC model." (NVC, 6)

The four components of NVC

- The concrete actions we observe that affect our well-being

- How we feel in relation to what we observe

- The needs, values, desires, etc. that create our feelings

- The concrete actions we request in order to enrich our lives (NVC, 7)

These are the basics of the NVC model in a nutshell. Understanding how to employ them in your relationships will require study. I encourage readers to consult the book to fully appreciate its power. At its core, NVC teaches us to identify true needs. All humanity draws from the same pool of needs. Once we can identify each other’s true needs, we begin to see the common humanity we share. This often requires being vulnerable and recognizing our own and others’ feelings. Here is a list of common human needs:

- Sustenance: Basic survival needs such as food, water, shelter, and rest.

- Safety: Physical safety, security, and protection.

- Love: Affection, intimacy, and emotional connection.

- Understanding/Empathy: Being heard, understood, and receiving empathy.

- Creativity: Opportunities for self-expression and creativity.

- Recreation: Play, fun, and relaxation.

- Belonging: A sense of community, acceptance, and connection with others.

- Autonomy: Independence, freedom, and the ability to make choices.

- Meaning: Purpose, contribution, and a sense of fulfillment (https://www.sociocracyforall.org/nvc-feelings-and-needs-list/).

Principles of Crucial Conversations

Here is a summary of the main principles outlined in Crucial Conversations:

- Start with Heart: Focus on what you really want for yourself, others, and the relationship. Stay true to your goals and avoid getting sidetracked by emotions.

- Learn to Look: Be aware of when a conversation becomes crucial. Pay attention to signs of stress or silence and recognize when safety is at risk.

- Make It Safe: Create a safe environment for dialogue. Establish mutual purpose and mutual respect to ensure everyone feels comfortable sharing their views.

- Master My Stories: Take control of your emotions by examining the stories you tell yourself. Separate facts from your interpretations and assumptions.

- State My Path: Share your views clearly and confidently. Use facts and describe your perspective without exaggeration or judgment.

- Explore Others’ Paths: Encourage others to share their views. Listen actively, ask questions, and show genuine interest in their perspectives.

- Move to Action: Turn the conversation into action. Decide on next steps, assign responsibilities, and follow up to ensure accountability.

What are Feelings?

Crucial Conversations (CC) is filled with examples and practical advice on communication. It reads like a great motivational self-help book, backed by studies and years of experience from skilled practitioners of the CC method. I was able to identify the principles in CC and relate them to similar ideas in Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (NVC). For example, CC emphasizes that being aware of one’s feelings is crucial for having an effective crucial conversation. In fact, chapter five in CC, “Master My Stories”, focus on this subject. It makes this important point:

"It’s important to get in touch with your feelings, and to do so, you may want to expand your emotional vocabulary." (CC, 87)

It was on seeing how CC dealt with the subject of feelings, that the key difference between the two books started to become evident.

An example is related in chapter three of CC, “Choose Your Topic”:

"I am the only nonwhite person on my team. I have been called by the wrong name multiple times in meetings by my immediate manager..."

Discussing ways for this person to decide how best to proceed, one option included:

"Talk relationship. Let your manager know that your name is an important part of your identity, and that you feel disrespected when someone you work with regularly doesn’t take the time to learn it. Or perhaps even more important, you feel disrespected by the suggestion that you change it." (CC, 44-45, emphasis mine)

Rosenberg would point out that “feeling disrespected” is not a true feeling:

"In NVC, we distinguish between words that express actual feelings and those that describe what we think we are.

Description of what we think we are:

'I feel inadequate as a guitar player.'

In this statement, I am assessing my ability as a guitar player, rather than clearly expressing my feelings.

Expressions of actual feelings:

'I feel disappointed in myself as a guitar player.'

'I feel impatient with myself as a guitar player.'

'I feel frustrated with myself as a guitar player.'

The actual feeling behind my assessment of myself as 'inadequate' could therefore be disappointment, impatience, frustration, or some other emotion.

Likewise, it is helpful to differentiate between words that describe what we think others are doing around us, and words that describe actual feelings." (NVC, 42)

On the following page, NVC provides a list of what we might call faux, or false feelings:

"Words like ignored express how we interpret others, rather than how we feel. Here is a sampling of such words:" (See NVC, 43)

| abandoned | co-opted | misunderstood | taken for granted |

| abused | cornered | neglected | threatened |

| attacked | diminished | overworked | unappreciated |

| betrayed | distrusted | patronized | unheard |

| boxed-in | interrupted | pressured | unseen |

| bullied | intimidated | provoked | unsupported |

| cheated | let down | put down | unwanted |

| coerced | manipulated | rejected | used |

How CC deals with the topic of feelings is elaborated on in chapter five:

"Actually, identifying your emotions is more difficult than you might imagine. In fact, many people are emotionally illiterate. When asked to describe how they’re feeling, they use words such as “bad” or “angry” or “scared” — which would be OK if these were accurate descriptors, but often they’re not. Individuals say they’re angry when, in fact, they’re feeling a mix of embarrassment and surprise. Or they suggest they’re unhappy when they’re feeling violated. Perhaps they suggest they’re upset when they’re really feeling humiliated and hurt. Since life doesn’t consist of a series of vocabulary tests, you might wonder what difference words can make. But words do matter. Knowing what you’re really feeling helps you take a more accurate look at what is going on and why. For instance, you’re far more likely to take an honest look at the story you’re telling yourself if you admit you’re feeling both embarrassed and surprised rather than simply angry. When you take the time to precisely articulate what you’re feeling, you begin to put a little bit of daylight between you and the emotion. This distance lets you move from being hostage to the emotion to being an observer of it. When you can hold it at a little distance from yourself, you can examine it, study it, and begin to change it. But that process can’t begin until you name it. How about you? When experiencing strong emotions, do you stop and think about what you’re feeling? If so, do you use a rich vocabulary, or do you mostly draw from terms such as ‘OK,’ ‘bummed out,’ ‘ticked off,’ or ‘frustrated’? Second, do you talk openly with others about how you feel? Do you willingly talk with loved ones about what’s going on inside you? Third, in so doing, do you take the time to get below the easy-to-say emotions and accurately identify those that take more vulnerability to acknowledge (like shame, hurt, fear, and inadequacy)? It’s important to get in touch with your feelings, and to do so, you may want to expand your emotional vocabulary." (CC, 86-87, emphasis mine)

CC nails it, while at the same time missing a crucial point that using a counterfeit feeling like “violated” is not a true feeling. This is a significant distinction in NVC. As pointed out above, words like “violated” and “humiliated” are evaluative words, not true feelings. Being “violated” invokes some form of judgement that would require a “violator.” For one to be “humiliated” requires there be a “humiliator.” Use of such terms increases defensiveness and resistance.

"A common confusion, generated by the English language, is our use of the word feel without actually expressing a feeling. For example, in the sentence, 'I feel I didn’t get a fair deal,' the words I feel could be more accurately replaced with I think. In general, feelings are not being clearly expressed when the word feel is followed by: Words such as that, like, as if: 'I feel that you should know better.' 'I feel like a failure.' 'I feel as if I’m living with a wall.' The pronouns I, you, he, she, they, it: 'I feel I am constantly on call." 'I feel it is useless.' Names or nouns referring to people: 'I feel Amy has been pretty responsible.' 'I feel my boss is being manipulative.' Conversely, in the English language, it is not necessary to use the word feel at all when we are actually expressing a feeling: we can say, 'I’m feeling irritated,' or simply, 'I’m irritated.'" (NVC, 41)

Building a Vocabulary for Feelings

CC encourages we expand our emotional vocabulary. NVC takes it further by compiling lists to help increase our power to articulate feelings and clearly describe a whole range of emotional states.

Feelings (Emotions) when Needs are Met

| AFFECTIONATE | EXCITED | GRATEFUL | PEACEFUL |

| compassionate | amazed | appreciative | calm |

| friendly | animated | moved | centered |

| loving | ardent | thankful | clear headed |

| open hearted | aroused | touched | comfortable |

| sympathetic | astonished | content | |

| tender | dazzled | HOPEFUL | equanimous |

| warm | eager | expectant | fulfilled |

| energetic | encouraged | mellow | |

| CONFIDENT | enthusiastic | optimistic | quiet |

| empowered | giddy | relaxed | |

| open | invigorated | INSPIRED | relieved |

| proud | lively | amazed | satisfied |

| safe | passionate | awed | serene |

| secure | surprised | wonder | still |

| vibrant | tranquil | ||

| ENGAGED | JOYFUL | trusting | |

| absorbed | EXHILARATED | amused | |

| alert | blissful | delighted | REFRESHED |

| curious | ecstatic | glad | enlivened |

| enchanted | elated | happy | rejuvenated |

| engrossed | enthralled | jubilant | renewed |

| entranced | exuberant | pleased | rested |

| fascinated | radiant | tickled | restored |

| interested | rapturous | revived | |

| intrigued | thrilled | ||

| involved | |||

| spellbound | |||

| stimulated |

Feelings (Emotions) when Needs are NOT Met

| AFRAID | CONFUSED | EMBARRASSED | SAD (cont.) |

| apprehensive | ambivalent | ashamed | heavy hearted |

| dread | baffled | chagrined | hopeless |

| foreboding | bewildered | flustered | melancholy |

| frightened | dazed | guilty | unhappy |

| mistrustful | hesitant | mortified | wretched |

| panicked | lost | self-conscious | |

| petrified | mystified | TENSE | |

| scared | perplexed | FATIGUE | anxious |

| suspicious | puzzled | beat | cranky |

| terrified | torn | burnt out | distressed |

| wary | depleted | distraught | |

| worried | DISCONNECTED | exhausted | edgy |

| alienated | lethargic | fidgety | |

| ANGRY | aloof | listless | frazzled |

| enraged | apathetic | sleepy | irritable |

| furious | bored | tired | jittery |

| incensed | cold | weary | nervous |

| indignant | detached | worn out | overwhelmed |

| irate | distant | restless | |

| livid | distracted | PAIN | stressed out |

| outraged | indifferent | agony | |

| resentful | numb | anguished | VULNERABLE |

| removed | bereaved | fragile | |

| ANNOYED | uninterested | devastated | guarded |

| aggravated | withdrawn | grief | helpless |

| disgruntled | heartbroken | insecure | |

| dismayed | DISQUIET | hurt | leery |

| displeased | agitated | lonely | reserved |

| exasperated | alarmed | miserable | sensitive |

| frustrated | discombobulated | regretful | shaky |

| impatient | disconcerted | remorseful | |

| irked | disturbed | YEARNING | |

| irritated | perturbed | SAD | envious |

| rattled | dejected | jealous | |

| AVERSION | restless | depressed | longing |

| animosity | shocked | despair | nostalgic |

| appalled | startled | despondent | pining |

| contempt | surprised | disappointed | wistful |

| disgusted | troubled | discouraged | |

| dislike | turbulent | disheartened | |

| hate | turmoil | forlorn | |

| horrified | uncomfortable | gloomy | |

| hostile | uneasy | ||

| repulsed | unnerved | ||

| unsettled | |||

| upset |

The Need for Safety

CC emphasizes the need to recognize when safety is at risk.

"If what we’re suggesting here is true, then the problem is not the message. The problem is that you and I fail to help others feel safe hearing the message. If you can learn to see when people start to feel unsafe, you can take action to fix it. That means the first challenge is to simply see and understand that safety is at risk." (CC, 112, emphasis mine)

Here CC has identified what could either be a common human need for “safety”, or an actual feeling, that of feeling “safe,” (which could likewise be expressed as feeling “confident,” “empowered,” or “secure”). On the other hand, if used as an expression of a universal human need, this would be another example that Rosenberg identifies in NVC, of the common confusion generated by the English language where the word feel is used without expressing a feeling.

In NVC it is an important distinction to be able to separate feelings from needs in order to truly connect with ourselves and others. Rosenberg points out in the opening chapter of NVC:

"NVC guides us in reframing how we express ourselves and hear others. Instead of habitual, automatic reactions, our words become conscious responses based firmly on awareness of what we are perceiving, feeling, and wanting. We are led to express ourselves with honesty and clarity, while simultaneously paying others a respectful and empathic attention. In any exchange, we come to hear our own deeper needs and those of others." (NVC, 3, emphasis mine)

In my own experience with learning NVC, the challenge of “reframing” has not been easy. It has taken a conscious practice to increase my awareness and vocabulary around feelings and needs, but the results have had a profound effect on my ability to navigate difficult conversations.

Earlier in the book, CC pointed out how:

"No matter how comfortable it might make you feel to say it, others don’t make you mad. You make you mad. You make you scared, annoyed, insulted, or hurt. You and only you create your emotions." (CC, 75)

NVC also confirms this idea:

"Another kind of life-alienating communication is denial of responsibility. Communication is life-alienating when it clouds our awareness that we are each responsible for our own thoughts, feelings, and actions. The use of the common expression have to, as in 'There are some things you have to do, whether you like it or not,' illustrates how personal responsibility for our actions can be obscured in speech. The phrase makes one feel, as in 'You make me feel guilty,' is another example of how language facilitates denial of personal responsibility for our own feelings and thoughts." (NVC, 19)

It is an important distinction to point out what CC is NOT saying. To the extent that we may imply that by our words we can “make” others “feel unsafe”, we imply something that is fundamentally untrue.

Earlier in this post we listed some common human needs that were identified in NVC. To the degree that CC treats safety as common human need, making it the main object is to prioritize it over other fundamental human needs. In practice, it is a difficult thing to learn the art of identifying needs. For me, I think prioritizing the need for safety over other equally important needs would hinder the intent of NVC to get to the true root needs. This is one reason I find focusing on the NVC approach to communicating much preferred over the model presented in CC.

What About Violence?

The final point I would like to make is to examine how the two books treat the topic of violence.

In CC violence gets defined:

"Violence consists of any verbal strategy that attempts to convince or control others or compel them to your point of view. It violates safety by trying to force meaning into the pool. Methods range from name-calling and monologuing to making threats." (CC, 117)

In NVC, “violence” is rooted in judgement. The concept is based on what one instructor of the NVC method referred to as the “John Wayne effect.” In this scenario, if you walk into a bar and meet someone who is a good guy, you buy him a beer. If he’s a bad guy, you either beat him up or shoot him:

"The relationship between language and violence is the subject of psychology professor O.J. Harvey’s research at the University of Colorado. He took random samples of pieces of literature from many countries around the world and tabulated the frequency of words that classify and judge people. His study shows a high correlation between frequent use of such words and frequency of incidents. It does not surprise me to hear that there is considerably less violence in cultures where people think in terms of human needs than in cultures where people label one another as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ and believe that the ‘bad’ ones deserve to be punished. In 75 percent of the television programs shown during hours when American children are most likely to be watching, the hero either kills people or beats them up. This violence typically constitutes the ‘climax’ of the show. Viewers, having been taught that bad guys deserve to be punished, take pleasure in watching this violence." (NVC, 17-18)

When our words are framed as blame or judgement, they become what Rosenberg calls “life-alienating,” which blocks compassion:

"Such judgments are reflected in language: 'The problem with you is that you’re too selfish.' 'She’s lazy.' 'They’re prejudiced.' 'It’s inappropriate.' Blame, insults, put-downs, labels, criticism, comparisons, and diagnoses are all forms of judgment. The Sufi poet Rumi once wrote, 'Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and right-doing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.' Life-alienating communication, however, traps us in a world of ideas about rightness and wrongness — a world of judgments." (NVC, 15-16)

So, to compare the two ideas, in CC violence “consists of a verbal strategy that attempts to force meaning into the pool,” whereas in NVC violence is the result of judgements that classify and label one another as “good” or “bad” where the “bad” ones deserve to be punished. Let me frame this as a question. To the degree that in NVC the word violence takes on a different meaning than how it is used in CC, is CC attempting to force a different meaning for this word into the pool, making its use of the word, by its own definition, a form of violence in itself?

From an NVC perspective, the key would be how the concept is communicated. If CC uses the term “violence” in a way that promotes empathy, understanding of underlying needs, and invites connection, it might not be seen as violence by NVC standards. But if it leads to judgment, blame, or disconnection, then one could argue it’s moving towards what NVC would consider violent communication.

Making Requests

One component of the NVC model is requesting that which would enrich life. Recall the four components of NVC:

- Observation

- Feelings

- Needs

- Requests. (See NVC, 6-7)

It’s typical for us to not want to have needs. We don’t want to be needy. We don’t want to expose ourselves to be vulnerable as someone with needs. Learning to ask for what I want has possibly been the most difficult part for me in learning and practicing NVC. The idea of making requests of others for what we need is an important element of the NVC model. NVC dedicates a chapter on “Requesting That Which Would Enrich Life”:

"We have now covered the first three components of NVC, which address what we are observing, feeling, and needing. We have learned to do this without criticizing, analyzing, blaming, or diagnosing others, and in a way likely to inspire compassion. The fourth and final component of this process addresses what we would like to request of others in order to enrich life for us. When our needs are not being fulfilled, we follow the expression of what we are observing, feeling, and needing with a specific request: we ask for actions that might fulfill our needs. How do we express our requests so that others are more willing to respond compassionately to our needs?" (NVC, 67)

To me this idea of making a request for my own needs is not expressly evident in CC, except where the authors identify the importance of determining what we really want:

"Choosing is a matter of filtering all the issues you’ve teased apart through a single question: 'What do I really want?'" (CC, 47-48)

"Clarity is crucial. But so is flexibility. Remember, this isn’t a monologue. It should be a dialogue. There are other people in this conversation, and they have their own wants and needs. In some Crucial Conversations, new issues will come up, and you need to balance focus (on your goals) with flexibility (to meet their goals)." (CC, 52)

Are you ask’n or tell’n?

Have you ever had someone make a request of you where you felt drawn to have them clarify (whether you actually expressed it out loud), “Are you asking me or are you telling me? Because if you are telling me, the answer is no.”

It seems to be a built-in human condition to resist being bossed around. In NVC, respect, acceptance, trust, and cooperation are examples of common human needs. NVC has a section in chapter six on “Requests versus Demands”:

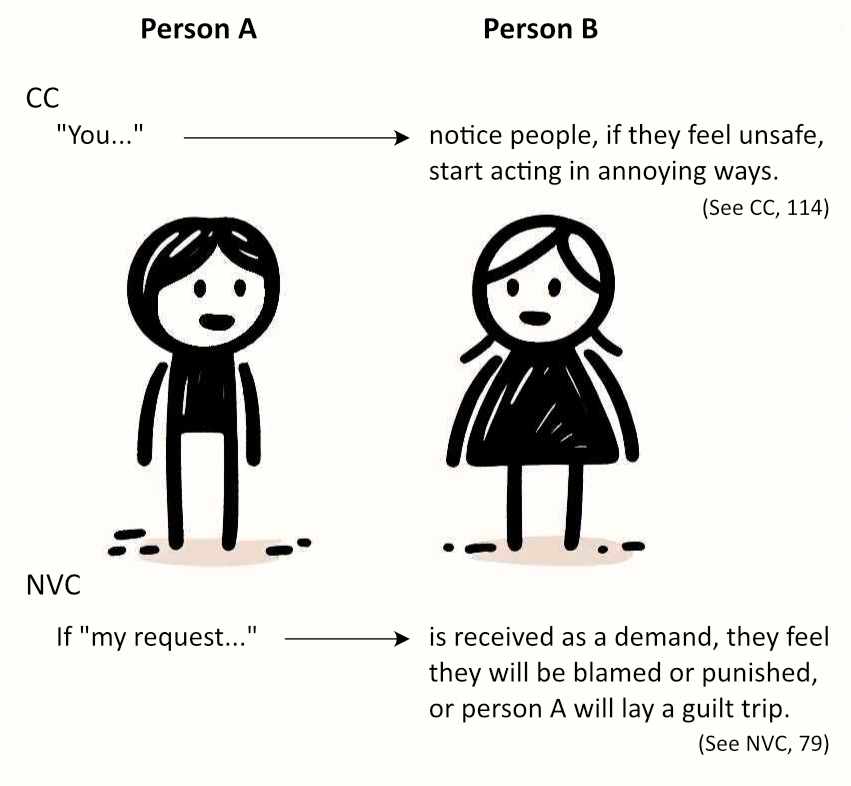

"Our requests are received as demands when others believe they will be blamed or punished if they do not comply. When people hear a demand, they see only two options: submission or rebellion. Either way, the person requesting is perceived as coercive, and the listener’s capacity to respond compassionately to the request is diminished." (NVC, 79)

The response others give to us when they perceive our request as a demand, appears to be the subject of what the CC model identifies as “feeling unsafe”:

"When others begin to feel unsafe, they start acting in annoying ways. They may make fun of you, insult you, or steamroll you with their arguments. In such moments, you should be thinking to yourself: 'Hey, they’re feeling unsafe. I need to do something — maybe make it safer.'" (CC, 114)

We see this idea emerge in how CC uses the terms silence and violence:

"Learn to identify the two kinds of behavior that will clue you in to the fact that someone’s feeling unsafe. We refer to them as silence and violence." (CC, 115)

NVC identifies two kinds of behavior when the other person perceives our request as a demand:

- When the other person hears a demand from us, they see two options: to submit or to rebel.

- To tell if it’s a demand or a request, observe what the speaker does if the request is not complied with.

- It’s a demand if the speaker then criticizes or judges. (Or lays a guilt trip)

- It’s a request if the speaker then shows empathy toward the other person’s needs. (See NVC, 79-80)

Where CC encourages “rebuilding safety,” NVC encourages “showing empathy”:

"When safety is at risk and you notice people moving to silence or violence, you need to step out of the content of the conversation (literally stop talking about the topic of your conversation) and rebuild safety." (CC, 133)

In NVC empathy is something that we may need to show toward others when we become aware that they perceive our request as a demand. Empathy is also something we may need to give to ourselves:

"We need empathy to give empathy. When we sense ourselves being defensive or unable to empathize, we need to (1) stop, breathe, give ourselves empathy; (2) scream nonviolently; or (3) take time out." (NVC, 104)

In CC the focus is on identifying the kinds of behavior exhibited by others that clue us in to when they may be feeling unsafe, so that we can then take steps to “make it safe” (See CC, 127). NVC wants us to recognize that we ourselves are just as likely to be the ones who need safety1:

"The more we have in the past blamed, punished, or 'laid guilt trips' on others when they haven’t responded to our requests, the higher the likelihood that our requests will now be heard as demands. We also pay for others’ use of such tactics. To the degree that people in our lives have been blamed, punished, or urged to feel guilty for not doing what others have requested, the more likely they are to carry this baggage to every subsequent relationship and hear a demand in any request." (NVC, 79)

Conclusion

Ultimately, the objective in both books is to give us tools to navigate the complexity of our relationships through improving how we communicate with others. This study has left me convinced that the effort I have spent in trying to master the tools of NVC has not been wasted. Though CC offers a great method on how to approach difficult conversations when stakes are high, for me NVC gets me closer to the heart of my true intent, in fact, my true “need,” for heartfelt connection with others. Once that can be attained, the issues that divide us tend to resolve themselves. From the chapter “Conflict Resolution and Mediation,” Rosenberg puts it this way:

"My experience has taught me that it’s possible to resolve just about any conflict to everybody’s satisfaction. All it takes is a lot of patience, the willingness to establish a human connection, the intention to follow NVC principles until you reach a resolution, and trust that the process will work.

In NVC-style conflict resolution, creating a connection between the people who are in conflict is the most important thing. This is what enables all the other steps of NVC to work, because it’s not until you have forged that connection that each side will seek to know exactly what the other side is feeling and needing. The parties also need to know from the start that the objective is not to get the other side to do what they want them to do. And once the two sides understand that, it becomes possible — sometimes even easy—to have a conversation about how to meet their needs." (NVC, 161-162)

- I think the ideas are presented sufficiently clear as stated above, but here in this footnote I explore the interpersonal interactions between the two models (CC and NVC) a little further:

Silence or Violence, Submit or Rebel

From CC Perspective

Person A identifies when “safety is at risk” when Person B responds in silence or violence (acts in “annoying ways”). You also want to be aware of your own behavior, “your style under stress” (see CC, 120). Are you interacting with silence or violence yourself?

From NVC Perspective

It’s not, How do I know Person B feels “safe or unsafe”. In NVC that’s not the question. In NVC the question is how does Person B know Person A is making a request or a demand? The answer is if Person A is judging or criticizing or blaming or laying a guilt trip. In words of CC, it is responding with silence (for example a guilt trip) or with violence (for example criticizing or blaming). If it is a demand, Person B is left to respond by either submitting or rebelling (which can be considered a form of silence or violence itself).

Defensiveness

In CC people who feel unsafe become defensive because of one of two reasons:

“You first need to understand why someone feels unsafe. People never become defensive about what you’re saying (the content of your message). They become defensive because of why they think you’re saying it (the intent). Said another way, safety in a conversation is about intent, not content. When people become defensive, it is because either: 1. You have a bad intent toward them (and they are accurately picking up on that). Or: 2. They have misunderstood your good intent.” (CC, 133)

Similarly, in NVC a person may feel they have only two options (submit or rebel) when they become aware the request is actually a demand. NVC encourages us to remove judgement (whether the “intent” is “good” or “bad”), and focus instead on using empathy to open and connect with each other and ourselves in a way that allows our natural compassion to flourish. In the case of Person A that might be to become aware of his own demanding language and change something about his approach using empathy. In the case of Person B that might be to sense the “submit or rebel” instinct that arises within her and let him know how she feels and how the demand he is making does not meet her needs. In NVC there are not just two options or reasons for defensiveness. “Safe” and “unsafe” are among many feelings one may experience. Safety is only one of many other needs we may have. There are more than only two reasons for resistance, defensive, and aggressive reactions. ↩︎